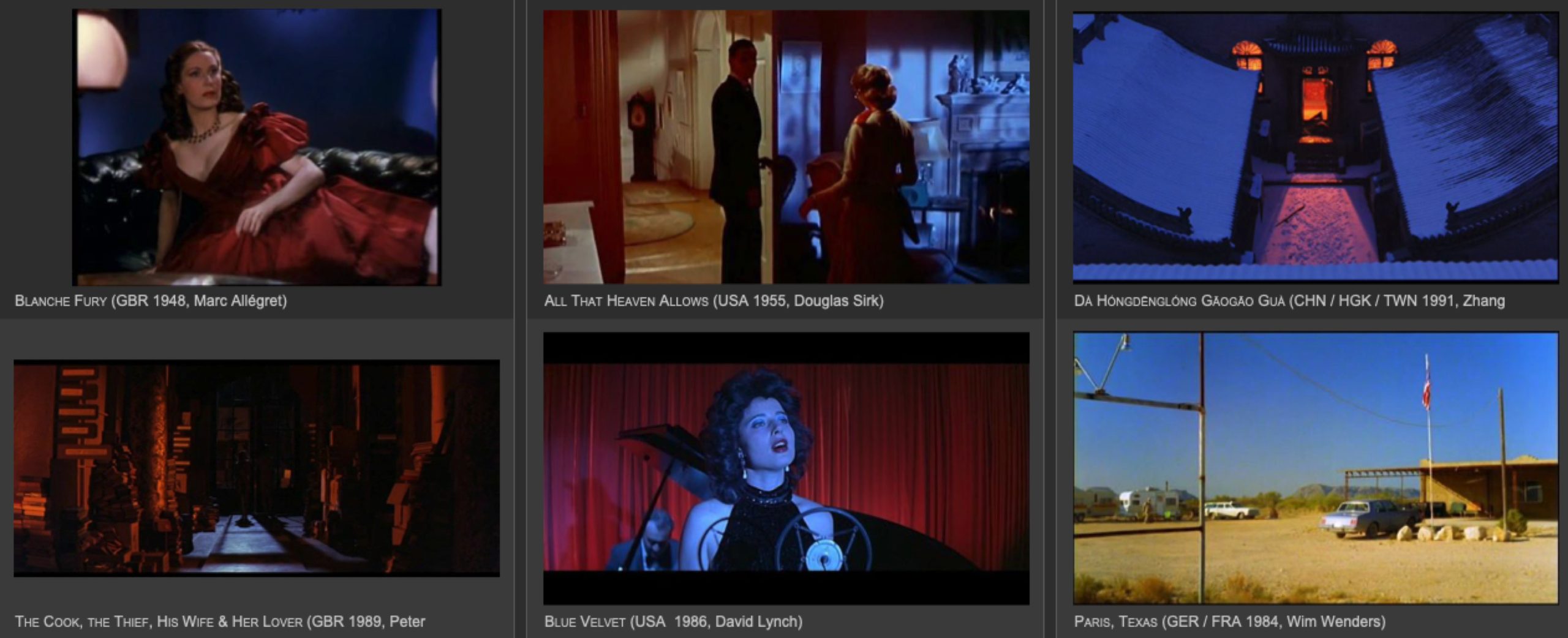

These past few weeks, I’ve been working on the Great Utopians project. It’s a relatively short database – 60 entries – that has received contributions from multiple researchers, compiling a list of thinkers and practitioners who, by their efforts for the radical improvement of society, have been designated as utopians. I’ve analyzed specific biographical data related to them – gender, nationality, place of birth, etc.

There is something very apparent when looking at the map: it’s astoundingly European – 48.3% of all entries, to be precise. That’s 29 Europeans out of 60 utopians. For comparison, there are four Africans. Four utopians, in a continent with 1.2 billion inhabitants.

Oh, that just means utopian thought is not a relevant field in Africa.

That doesn’t sound right. Do African thinkers not believe the world can be improved? I believe the problem is with us – we, in academia, who define ‘valid thought’.

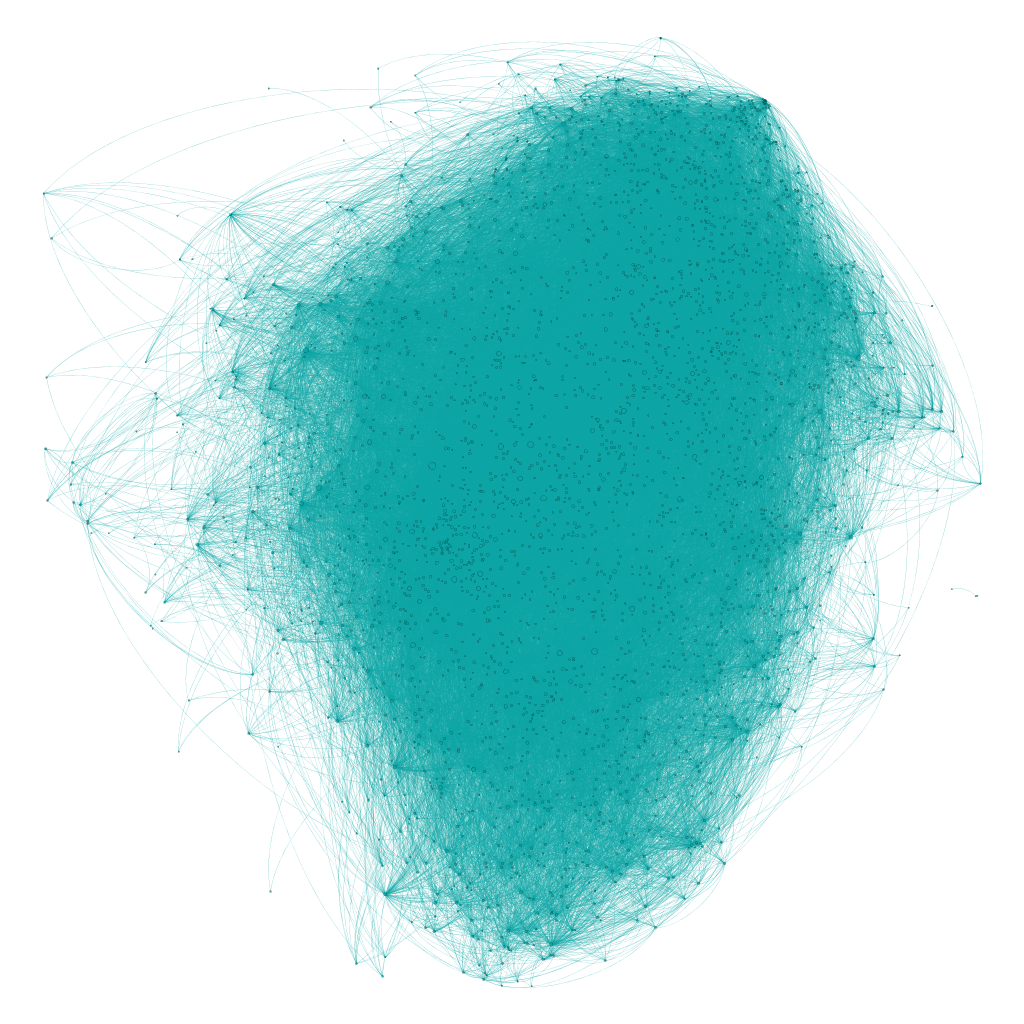

The Great Utopians world map. Each marker represents a person designated as a Great Utopian for their contributions in advancing our world and bettering society.

Edward Said argued that, because the Enlightenment – a phenomenon occurring when Europe quite literally ruled the world – laid the foundations for the creation of the social sciences, an idea of Europeans as arbiters of logic is deeply ingrained in our minds. In essence, ‘knowledge producers’ work within borders defined by colonial Europe.

As researchers, we are inheritors of the Enlightenment, so it stands to reason that we would unconsciously inherit this philosophy that sees Europe as the civilizational model of the world. Allow me to be unoriginal and mutilate James Carville’s iconic phrase:

It’s Eurocentrism, stupid.

But why does Europe define ‘worthwhile thought’ for all peoples, and how do we fix this issue? For this, I suggest we look to historian Enrique Dussel’s essay ‘Europa, Modernidad y Eurocentrismo’.

To start, Dussel argues that European identity defines the continent as inheriting a perceived civilizational continuum beginning with Classical Greece, going through Rome, Byzantium, and Medieval Christendom, and ending at the Renaissance. All these civilizations fundamentally ‘otherized’ neighboring cultures – Thracians, Celts, Muslims, etc. Modern Europe then applied this logic to people worldwide during its colonial expansion.

The maturation of Eurocentrism then came from Modernity being defined as the product of four European events – the Renaissance, the Reformation, the French Revolution, and the Industrial Revolution. This has made it so Modernity is seen as an equation of exclusively intra-European phenomena.

All these events made Europe the nucleus of Modernity and the expanding force that ‘modernizes’ the periphery. Thus, Dussel characterizes Modernity in the following terms:

- Modern society sees itself as more developed (and Modern society = Europe);

- Developmental superiority demands that ‘primitives’ be developed by their ‘superiors’:

- The path towards development should emulate the one taken by Europe.

It seems we should attempt to fix this issue to create a fairer philosophy of history – if not to try to make the world fairer.

Dussel argues we must recognize the European civilizational continuum as a myth – based upon ideas of European cultural exceptionalism – and our understanding of Modernity as incomplete when we define it exclusively by European phenomena. It then becomes apparent that it’s wrong to equate ‘European civilization’ with an ideal matrix that should be forced upon the world. Modernity cannot be actualized by imposing “Europeanness”, but by transcending Eurocentrism and recognizing that the Modern world is built by all peoples. This, Dussel says, is a recognition of the dignity of the Other.

The Digital Lab is built upon the field of Digital Humanities, which distinguishes itself from traditional academia by its special focus on pluralism and diversity. A Eurocentric philosophy of creating thought will deafen us to the contributions of valuable voices worldwide, not just the ones that adhere to ‘correct’ ways of thinking. How can we create a pluralistic and diverse field of research if we don’t allow ourselves to cut the umbilical cord connecting us to Mother Europe, the entity that swallowed the world, spat it out, and told it how to think?

Dussel’s maxim should guide us: recognizing the dignity of the Other; to those who study utopia, this means recognizing the validity of those civilizational matrices in the “periphery” of the world and, by extension, the unique utopian structures such realities may generate.

You can read Enrique Dussel’s essay here. It’s in Spanish, so good luck with that.